Support mechanism

Even the most detailed crisis plan in the world cannot prepare you for the reality of dealing with a tragic death. John Caperon looks at the emotive leadership qualities needed to see a school or college community through grief and loss.

When I was newly appointed to the senior team, I was occasionally plagued by fantasies of screaming tabloid headlines, all exposing some dreadful policy failure or educational disaster for which I alone was responsible. Paranoid symptoms, perhaps, but my guess is that most senior colleagues have been there, or somewhere near it. The fact is, a position of responsibility in a school or college is scary business, even at the best of times.

And what about the worst of times? How do we respond when things do really go drastically and appallingly wrong - not because of some failure on our part, but because of some external tragedy or other event entirely beyond our control?

The sobering fact is that every ASCL member, in all probability, is going to confront a disaster, a tragedy or a death in the community at some point in his or her tenure. Some will have to manage the unimaginably dreadful.

Three sixth form students are killed in a car crash. A popular young teacher dies suddenly of a rare disease. A year 10 student commits suicide. Two year 12 students on an adventure expedition in Latin America fall to their deaths. A senior colleague is murdered at the school gate.

These are all real events - not products of the paranoid imagination - which will merit a mention in the national media, and which the rest of the educational world will react to with shock, compassion and a sense of both solidarity and secret relief.

Something like this - the dire statistics of mortality being what they are - is pretty sure to happen to all of us sooner or later.

At times like these our leadership and management skills are at or beyond full stretch.

And no doubt we are all prepared, at least at one level. The disaster plan is on the shelf, and we have dusted it off from time to time.

We know exactly what the lines of responsibility are: who phones the chair of governors; who liaises with the media; who keeps in touch with parents. We know who arranges for counselling staff to be brought in and who writes letters of condolence; who keeps the school or college running 'normally' while the crisis is being managed.

But beyond the administrative and managerial dimensions - and we must have these professionally covered whatever happens - there is the whole human dimension to handle.

There is information to be shared in a sensitive and informed and appropriate way with colleagues and students. There is the shock and grief of both students and staff to deal with. There are traumatised parents who will need at least some of the school's care and concern. There are caring staff whose personal resources are taken to the limit and who need care themselves.

This is where senior team members must be people of understanding and empathy, not simply leaders and managers. We need to have real insight into what the experience of sudden loss feels like. We need to be able to lead staff meetings and assemblies, for example, with the tact and skill which enable staff and student shock and grief to be acknowledged, recognised, shared and calmed.

We need to be able to respond with humanity and compassion to personal grief in those around us - to know, for instance, when to cover a colleague's class because he is overcome with emotion and just can't face students, when to embrace a bereaved parent.

Making time for grief

Part of our leadership will be about giving permission to the community - encouragement, even - to grieve together. Students may well need time and space in the classroom to reflect upon events and to respond to them.

There are obvious contexts where this can happen - in English, say, with the help of poems and stories, or in RE lessons - but all subject teachers need to be aware of students' need to think, to imagine, to weep, to comfort one another.

And there is an important place for collective grief, the public sharing of the whole community's mourning. Whatever the religious or secular identity of the school, this is where the provision for 'collective worship' can be used positively.

Perhaps religious schools have an easier task in managing collective expressions of grief and loss: they have a common framework of belief; there are well-known, understood, liturgical forms in which ultimate matters of life and death can be handled.

But all education communities can create their own liturgy, drawing on familiar, sacred words, using common rituals and symbols - lighting candles, reading poems, giving personal tributes - out of their own experience and resources.

The school or college may also need to find a place for quiet contemplation, for grief, prayer and renewal. Few places are equipped with chapels or quiet rooms - official religious spaces. Perhaps, then, a community in mourning may need to designate a space, at least for a time, where students or staff may withdraw to grieve or pray or simply reflect.

Permanent memorial

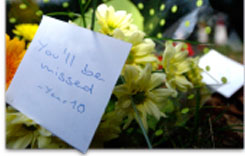

And what about commemorating the person or people whose lives have been part of the school but are no longer? Just as there has been a revival of popular liturgical expression in the lighted candles and votive flowers and gifts that mark a scene of death, so there may be a place for celebrating a lost colleague or student with a memorial plaque or garden or tree. Surely, if we value every member of the community, we need to mark the loss of that member in some tangible way.

Leadership teams have a tough enough time doing the day-to-day job of leading and managing; human tragedy, death and bereavement add a huge further burden to their responsibility that cannot take second place to inspections or exam time.

This is where heads, principals and senior colleagues are called upon to be, above all, people of humanity, identifying with their community's loss but also finding the ways in which that loss can be properly acknowledged and responded to.

This is a profound kind of spiritual leadership, really. And a school or college leader's greatest challenges may not be in the realms of strategy or structure or even the shape of the school curriculum, but of spirituality.

Sustaining leadership in these circumstances, providing the extended community and all its members with the support and framework for grief which it needs, is an exacting calling.

John Caperon is a former headteacher who is now Director of the Bloxham Project, as well as an ASCL Consultant.

Acknowledging tragedy

Communities that have been touched by tragedy need time and space to come to terms with loss. Leaders can help by:

Creating a quiet space for students and staff when need they to grieve, remember or reflect, and giving them permission to use it at any time.

Gathering the whole school or college community together to publicly acknowledge grief and loss.

Encouraging students to express feelings and emotions as part of classroom work, such as poetry, artwork, song or drama.

Remembering and commemorating lost community members during annual events including concerts and end of year activities.

Creating a permanent memorial with a garden, tree or plaque.

© 2026 Association of School and College Leaders | Designed with IMPACT