Reading between the lines

Opponents claim the use of fingerprint and other biometric technology in schools risks infringing children's civil liberties but their accusations are wide of the mark, argues ASCL member Brian Rossiter.

The use of biometrics is not new in schools. For the past decade libraries and learning centres have been installing fingertip scanners as an alternative to library cards for students and staff. It is only recently that headlines decrying the use of student 'fingerprints' and a small number of pressure groups have begun to oppose the use of biometrics in the name of 'protecting our freedoms'.

Historically, teachers used pen and paper to register students. This turned into the use of optically marked register sheets and, subsequently, to electronic registration systems such as Bromcom and SIMS Lesson Monitor.

In dining rooms many of us have sought ways to issue free meals to students confidentially and to speed up payments at serving points. Equally, we have looked for more effective systems to deal with loaning books and equipment in our resource centres. ("Sorry, James - you have six novels out at the moment, I think we need to talk about getting some back first?").

The common feature in all of these systems is finding a method of identifying the student or member of staff accurately and quickly, recording the data and having the data available for follow-up use.

Students' presence in class, allowance for free school meals and entitlement to take out a book on loan are examples of where newly developing ICT systems can support schools.

There are alternative solutions to the issue of student or staff identification. Simple cards that can be swiped through a card reader (like the pre-'chip and pin' credit card reader) were are an inexpensive physical method. They are often combined with a student ID card and store the relevant information on a barcode or magnetic strip.

Proximity cards perform the same functions but instead of swiping they have only to be placed near an appropriate reader. These more commonly occur in the form of 'Oyster' cards on the London Underground. They are more expensive than swipe cards but the mechanics of the reader are much more robust.

Both swipe card and proximity card systems rely on the student or staff member not losing their cards - and a system of replacement cards should this happen. This imposes running costs beyond simply installing the equipment and software.

Biometric systems offer schools a cost-effective way of moving away from a manual or card-based registration, library lending or catering service process.

Essentially, biometrics takes two different forms: the retina or iris recognition systems such as those being trialled at some airports; and fingertip recognition systems. It is the second of these that is being further developed for use in schools and which has attracted protests from some quarters.

When entering the classroom, learning centre or canteen, students who want to register, borrow a book or claim a free meal, place a finger on the digital fingertip scanner. Software then does the rest and, in less than a second, their identity is verified.

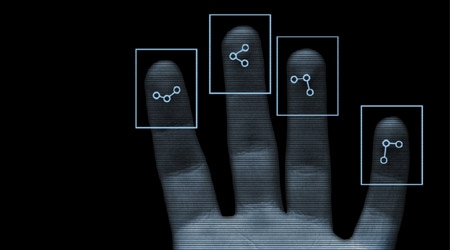

How the technology works

To be able to counter the criticisms of opponents, it's important to understand how the technology works.

There are two elements in the use of biometrics: enrolment (capturing the initial data on an individual) and verification (reading unknown data and matching it to data about individuals already on the system).

The core of the equipment is an optical scanner plus a biometric software application. Before the system goes live, each student has to be registered on the system.

Usually the system provider comes into school and organises to scan one fingertip of every student (and often a second as a reserve). When a student places a finger on the scanner/reader, a light on the reader illuminates the fingerprint. The scanning device then takes a 'photograph', or 'captures the image.

On a camera the image data would be stored so that the picture can be reproduced again and again. On the fingerprint reader most of the data is discarded and only a limited number (about 120) of random points on the fingerprint are retained. These are not stored as images but are converted using a complex mathematical process (an algorithm) to convert the image data to what is, essentially, a string of random numbers and letters.

This string, which is unique to the specific individual, prevents impersonation. The software used to encrypt this string is then tied to the name/data/information from SIMs or other management information software.

It would be extremely difficult to reverse the process to retrieve the image data but even if that were achieved, it would reveal only the 120 random points of the fingerprint. It is impossible to recover the whole fingerprint image. It is this point that I believe is misunderstood by opponents.

Once enrolled on a system, students can use the data to confirm their identity each time they put their 'enrolled' finger on to a reader attached to an ICT system. The data is as secure as any other management information data in school. When students leave, the fingerprint data should be destroyed.

Several companies have come to a schools' biometric market that is expanding quickly.

EasyTrace has a random six point system that is currently used for their cashless catering process. VeriCool also has a cashless catering package (120 point) as well as packages for multi-lesson registration/attendance monitoring which link dynamically to schools' SIMS.net software. Micro Librarian Systems' Eclipse 2000 library software has its own unique finger identification package.

The principle of 'collect once and make transferable to many different applications' is relevant here. Currently a national programme of inter-operability is being developed which will mean that data can be used in different hardware packages, irrespective of which one was used to capture it.

Biometrics in practice

One advantage of biometric systems is their ease of use. When I want to take a book out of our learning centre I simply put my finger on the reader and am identified. My book is then 'swiped' and I can take it away. When we introduced it six years ago the issue was not controversial and we have simply got on with it.

Likewise, cashless catering vending does not require a student to carry a swipe card or money to the till. Before buying anything, a student charges their account. Pre-payment methods include cheques, BACs or ParentPay into the caterer's account. Cash can also be paid into the account through a wall-mounted coin and note loader using fingertip verification to ensure the money goes into the correct user account. Students entitled to free school meals have their accounts credited as part of the software package.

At the till, students place their finger on the fingertip scanner to pay. Once successfully verified their account is debited. It really is that quick and simple, and the benefits are clear to the students, staff and school when they see it in action.

Convenience aside, it also ensures that money provided by parents to pay for schools meals is used only for that purpose! Increased revenue, profitability, and throughput of students becomes the norm using this technology and, because of the speed and ease of use, a reduction in service time in the school canteen is quite common.

Registration is equally simple. Systems such as VeriCool have a USB fingertip reader that plugs into the teacher's laptop. Other systems have hardwired wall mounted readers.

In both cases students put their fingers on a reader when they enter the room to register into a lesson. This data is then fed back to software and the attendance record updated. Schools can set times after which students are judged to be 'late' to register and follow up centrally if necessary.

Some teachers consider calling a register to be a key element of the job. But using biometrics gives time for the teacher to develop that relationship with their students in a different way. Schools using the technology also report better attendance rates as the student becomes responsible for ensuring they are in class and on time.

My school is part of an extensive PFI project in Nottinghamshire. As part of the project we have had many lengthy debates about cards (swipe versus proximity) and the use of biometrics.

We were asked by the contractor (Transform Schools, Bassetlaw) about our preference as they were preparing to install a cashless catering package in our dining rooms. The overwhelming issues of lost cards, the admin involved in replacing them and the cost to students who could ill-afford to pay for replacements led us to support the use of biometrics.

As the new schools in this area have opened they have all done so with finger identification installed. I believe our decision has been justified.

Parental concern

I believe strongly that parents should be properly informed of any proposal to introduce or extend biometric systems and I strongly recommend that all parents are consulted early before implementation begins.

For parents who do not want their child to be enrolled on a biometric system, there are usually override options so that these students can still be registered in class or buy food in the canteen using a manual verification process.

To support schools, the Information Commissioner is currently developing guidance for the use of finger recognition by non-police organisations. This includes working with parents.

The use of biometrics is becoming part of our normal daily life. A number of laptops are available with fingerprint scanner security built in. We will shortly have passports with basic biometric details included on a chip.

The development of this technology in schools is not new but the possibilities for reducing bureaucracy and increasing efficiency make it an option worth considering.

And after reading this article, I would simply ask that when you read screaming headlines about 'Fingerprinting our children' and 'Invasion of privacy' you simply reflect on the reality: a string of random numbers and letters.

Brian Rossiter is head of Valley School, a specialist technology college in north Nottinghamshire.

References

-

VeriCool - www.vericool.co.uk

-

Easytrace - www.easytrace.co.uk

-

Eclipse 2000 - www.microlib.co.uk

-

Becta - September 2006 TechNews - pages 11 to 15 - www.becta.org.uk/technews

-

The Information Commissioner - www.ico.gov.uk

-

Transform Schools - www.transformschools.co.uk

© 2026 Association of School and College Leaders | Designed with IMPACT