An emotional journey

Harnessing the power of emotional intelligence can improve staff and pupil performance in untold ways. Yet it's easy for leaders to overlook some very basic emotional needs, undermining other efforts to motivate staff and foster goodwill.

If you want to change a person's behaviour, "begin with praise and honest appreciation". So advised Dale Carnegie in 1936, in his eminently practical book How to Win Friends and Influence People.

In the last 70 years, Carnegie and those who have come after have been making the case that understanding how people's emotions affect their behaviour - now labelled emotional intelligence - is a key skill needed to manage people successfully in both the private and public sector.

Instead of assuming that all behaviour should be rational, it is now understood that we, and those we work with, are deeply influenced at all levels by emotions in ways that we cannot escape.

Once the power of emotional intelligence is harnessed, we begin to see that everyone - students and staff alike - can perform well beyond expectation in a truly exciting way.

The analytical work on emotional intelligence carried out by neuroscientists such as Daniel Goleman, Joseph Ledoux, Antonio Damasio and others offers a body of thinking about our own development which is, in the light of current medical research, unassailable.

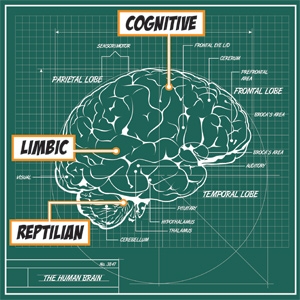

The three-part brain

There are different models for presenting ideas about emotional intelligence, but the key concepts are alike. We share emotions with animals. These originate in the limbic system of the brain, which helps regulate emotion, memory and certain aspects of movement. Long-term memory and sense of identity seem to be located in this system.

This enfolds the reptilian system - that part of the brain where almost involuntary responses take place. The instinct to fight or flee, to engage or dissociate, is determined by the state of the reptilian brain. Emotions are more sophisticated systems, but are also at the mercy of what happens in the reptilian brain.

Above the limbic system sits the neo-cortex, where cognitive processes occur. This capacity is what differentiates us from other mammals.

But, expressed starkly, the most sophisticated cognitive intelligence can be shut down or disabled by panic or anger: emotion can trigger the basic fight/flight response and make reasoning helpless.

Managing emotional reactions

However, we know and probably recognise from experience, that the more emotionally resilient and mature we are, the better able we are to minimise that emotional reaction - although we should always assume that the fight/flight reaction has taken place, just as surely as terror raises the heart rate or physical shock pumps adrenalin around the body.

Eventually, the human system insists on working as it has evolved to do, protecting us from stress by enforcing rest once it has removed us from danger.

However, our biology ensures that we are not completely at the mercy of our emotions, for we respond intuitively to the influence of others.

Whilst we may have difficulties in turning off our emotions on our own, being with someone else who is attuned to us or - more importantly - has the skill of attuning others to themselves, often allows us to manage emotion for ourselves more effectively than we can alone. Parents soothe a crying child; taking a colleague to a stressful meeting helps to keep anger or frustration in check.

One effective way of changing behaviour, overcoming emotional reactions or breaking habits is to associate with people who are strongly influential. This effect can be seen in 'herd behaviour'. Groups gravitate together: from gangs to armies, from friends to fellow workers, we are all affected by the emotional atmosphere.

In adults, the emotional demeanour of leaders has huge influence on the wellbeing of the rest of the staff - an influence that the analysts now try to quantify through their research into emotional intelligence.

So what are the implications of this for schools and colleges? For staff, it means realising that the behaviour of adults is deeply influential on the student body. Adults take the lead in creating the culture for learning, whether they intend to or not.

The behaviour of the leadership team is deeply influential on the rest of the adult body. This is subtle but real and can include:

-

enabling everyone to find a place and a role or, the opposite, colluding with a climate of exclusion

-

encouraging everyone to try out, to learn, and to profit by what has been learned (whether it be the results they want or the less convenient results that they do not want) - or generating a climate of anxiety and caution

-

creating a safe environment where the reptilian brain is happy - or allowing a culture of nervous correctness to dominate

A happy brain

Keeping the reptilian brain happy is the first task of the leadership team in relation to all the adults as well as students, visitors and others in the community. Taking care of everyday needs means that you will ensure a minimal level of efficiency and competence. If you ignore them, the consequences may prove to be expensive and time-consuming.

To keep the reptilian brain happy, some apparently simple factors need attending to. The reptilian brain wants:

-

its own territorial space. This means a physical space, however small, which belongs to the individual and where belongings can be safely kept

-

physical comfort - warmth, light, adequate refreshment and rest

-

a sense of belonging and the rituals which confer and endorse this

-

the feeling of safety, both physical and emotional. Reducing anxiety makes it more possible for the cognitive function to be at its highest

Most staff in schools and colleges will see the good sense of these statements - and they echo Maslow's hierarchy of human need (see On the road to somewhere) and yet when we look at the working conditions for adults and students we can see how many heavy unintended barriers are set up.

How are part-time staff treated, for instance? In some institutions, they are almost wholly peripatetic.

Is the staff room made inviting for all? Is the school/college day conducted at a hectic pace with little time for rest or reflection? Those who do take time to sit and think can sometimes be made to feel inadequate or lazy. Time spent on the 'rituals' can be seen as 'not teaching' and therefore 'not valuable'.

How are supply staff managed? Although they often respond to an urgent request for help, in some schools the message that supply staff receive on arrival is that they are not wanted - both by students who resent the absence of the regular teacher and adults who are too busy to make it possible for supply staff to do the job well. A reception which makes them feel wanted and secure can be well worth the time invested in the long run.

Equally, time spent on welcoming occasional members of staff and members of multi-agency teams, for instance is hard to find in the timetable of busy leadership team staff or office managers.

Such visitors sometimes report that they feel lost or out of place. This does not mean that their work is poor, just that an unnecessary barrier has been placed in front of them. They need to develop emotional resilience of their own to deal with it.

The ability to understand and manage oneself is a set of competences that grows over time. Insight into how others behave is developed with experience - with feedback as well as reflection.

We recognise that good mentors induce a sense of security and peacefulness and good teachers create an ambience of trust, so that students feel comfortable when asking questions. Such staff are making use of the feedback loop of the limbic system, whether or not they intend to do so.

This article was taken from the ASCL book New to the Leadership Team (2008), by Jill Clough and Harvey Black.

Change people without arousing resentment

A manager's job often includes changing people's attitudes and behaviour. Here are some suggestions to accomplish this:

-

Begin with praise and honest appreciation.

-

Call attention to people's mistakes indirectly.

-

Talk about your own mistakes before criticising the other person.

-

Give the other person a fine reputation to live up to.

-

Ask questions instead of giving direct orders.

-

Praise the slightest improvement and praise every improvement. Be "hearty in your approbation and lavish in your praise."

-

Let the other person save face.

-

Use encouragement. Make the fault seem easy to correct.

-

Make the other person happy about doing the thing you suggest.

From Dale Carnegie in How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936, reissued 1998)

© 2026 Association of School and College Leaders | Designed with IMPACT